As writers, we look for meaning in just about everything. Our lives are woven with metaphors and significance, often in objects, random images, or bits of conversation. We wonder what’s underneath the surface, and, because we are writers, we ponder and wrestle to make something of it.

Years ago, I searched for toothpicks in the supermarket, which I thought was a logical place to find them. I looked in the baking aisle because people use toothpicks to test a cake. No toothpicks. I looked in the vegetable section, thinking people use toothpicks to hold canapés together. Nope. I checked the section for drink mixers picturing olives in martinis. No dice. I went to the hardware aisle remembering my father using toothpicks for shims or breaking them into small bits as filler in furniture repairs. Nothing. I wasn’t particularly frustrated, because I do like the thrill of the hunt, but I was increasingly puzzled. The lure of the search and discovery is another fine trait we writers share. But I had limited time, so I broke down and asked a store clerk. Now, asking for help is not only a reasonable part of any research, it can also lead to rich and unexpected interactions. The clerk led me to household cleaning products and pointed to the top shelf. Next to the row of bottles and cans of furniture polish were the toothpicks. I was baffled. “Why are they here,” I asked. The clerk looked at me as though I was rather dim, and said, “Because they’re wood.”

I have considered that answer for years. First of all, it is downright poetic and a gift at the end of my determined exploration. I continue to find those words incredibly funny and satisfying. The why of where toothpicks should be stored is a question leading to the profoundly infinite logic we humans use to act out our lives. I also realized that an adventure contains a likely surprise if we let it find us. But I think my favorite meaning is that even a toothpick can lead us deeply into ourselves and an understanding of others. “He who has a why to live can bear with almost any how.” Friedrich Nietzsche

Upcoming Events

Open Spots in Weekly Writing Workshops:

These three-hour workshops offer the belief that every writer is developing their craft, that respect is the foundation of all artistic support, and that each session is a time for serious and playful exploration and experimentation. Workshops include the opportunity for a manuscript review. Please join me! maureen@maureenbjones.com

Tuesday Mornings 9:30 – 12:30 EDT Online September 13 – November 15, 2022

Friday Mornings 9:30 – 12:30 EDT Online September 16 – November 18, 20222

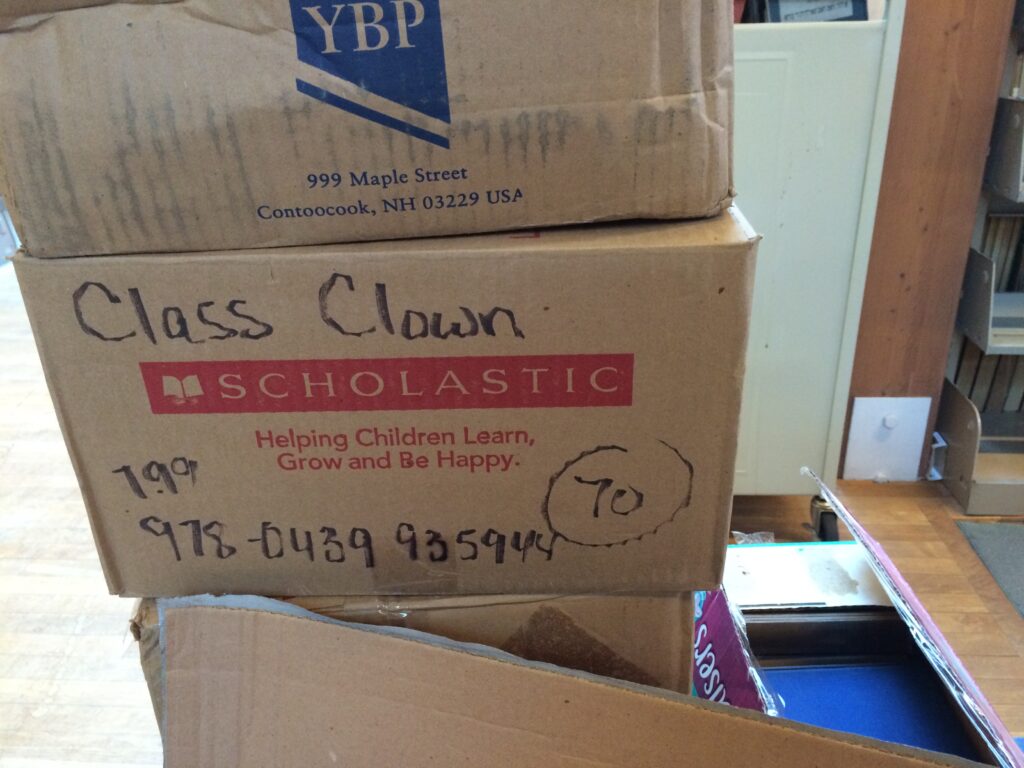

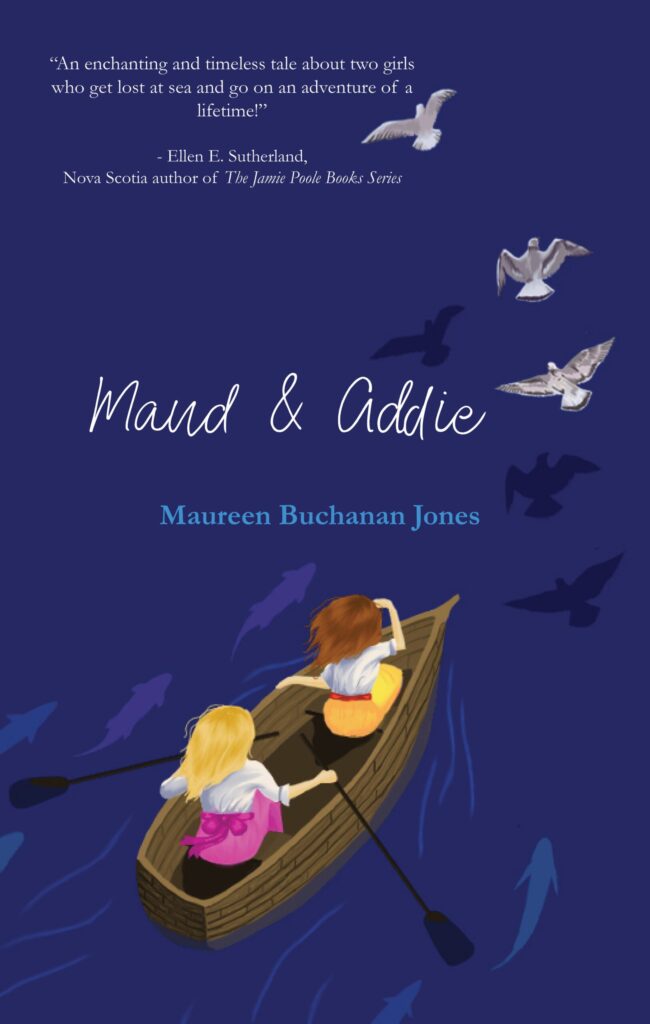

Photo Prompt